Interest rate sensitivity III/V: Are interest rate hikes non-events for assets?

The expectations are set. The market anticipates up to five interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve by the end of this year. These developments entail investment opportunities and risks for multi-asset investors. Part III of our five-part series on interest rate sensitivity.

Text: Claude Hess

Inflation had long been forgotten and even declared dead, but now it is back. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on international supply chains, the trend towards de-globalisation and the expansionary monetary policy practised by central banks for many years now, interest rate hikes appear imminent. But what does this mean for multi-asset investors?

Implications of rising interest rates on asset classes

A look back in time helps to better assess the effect of interest rate hikes on various asset classes. Nevertheless, analysing historical financial market conditions is not sufficient for determining future price developments of asset classes.

Aware of this fact, we have examined the period from 1973 to the present day and tracked how various asset classes performed on average from the perspective of a US investor before and after an interest rate hike1:

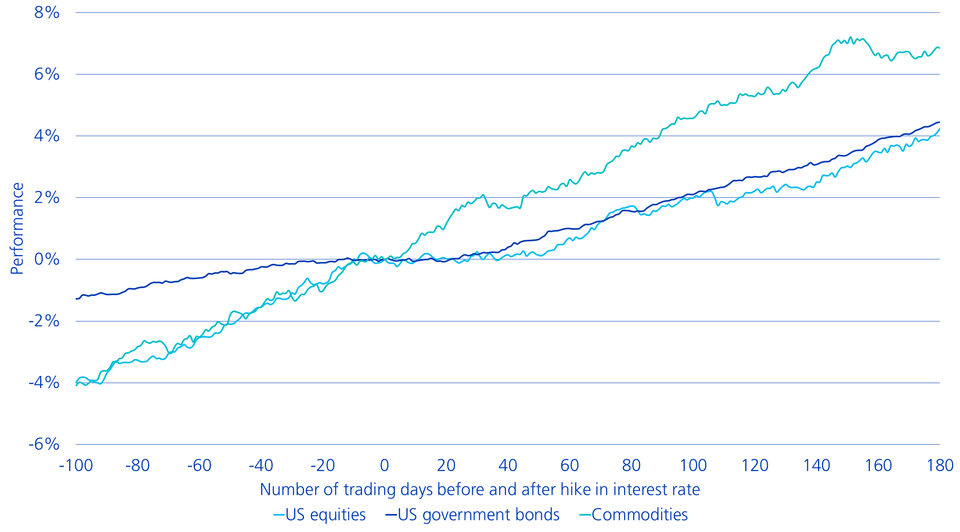

Average development before and after a US interest rate hike (1973-2021)

The chart shows that the common fear that interest rate hikes would depress equity markets has not materialised in the past. The equity markets tended to rise before an interest rate hike and then moved sideways for a while before continuing their rise. The same applies to bonds. In commodities, performance was best on average after an interest rate hike.

Monetary policy before and after the turn of the millennium

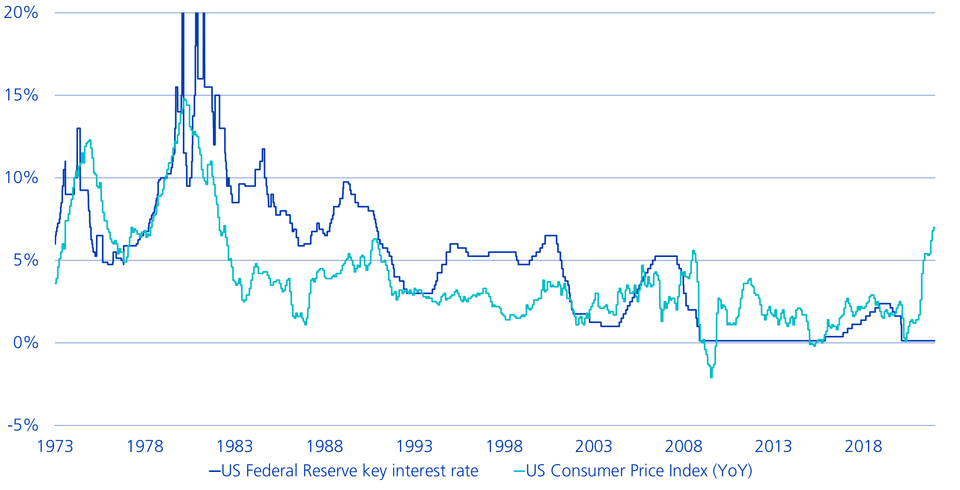

Inflation was very low from the 2000s onwards. In the USA, it was around 2.2% on average. This allowed central banks to pursue a much more expansionary monetary policy than in previous years. The unexpectedly vibrant renaissance of inflation mentioned at the beginning caught central banks on the wrong foot. The difference between the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Fed's targeted key interest rate has never been greater than it is today since 1973, as illustrated by the chart:

The speed of the rise in inflation is comparable to periods from the 1970s. However, at 0.125%, the current key interest rate is (still) extremely low compared to the current inflation level of over 7% in the USA and more than 5% in the euro area. For comparison: with similar inflation rates in the 1970s, the key interest rate at the time was around the level of the inflation rate or slightly higher. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that even between 1973 and 1999, the asset classes considered performed positively on average after interest rate hikes.

Including economic cycles in the analysis

Does this mean that interest rate hikes are non-events for equity markets? A more differentiated picture emerges with the inclusion of economic growth. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Fed raised interest rates in spite of the recession due to high inflation. Equity markets suffered more during this period. After 120 trading days, they lost an average of around 5%.

Average development before and after a U.S. interest rate hike during recessions (1973-2021)

This can be used to deduce that a stagflation scenario in which central banks are forced to raise interest rates due to inflation, even in times of negative economic growth, would be the least favourable for the equity markets.

Including balance sheet reductions in the analysis

There is also the question of how an interest rate hike combined with a balance sheet reduction by central banks affects the markets. Such a situation occurred in the USA in the fourth quarter of 2018. At that time, the markets reacted negatively to interest rate hikes, even though there was no recession. Since the 2008 financial crisis and during the coronavirus crisis, the balance sheet of the Fed and other central banks has expanded considerably. Reducing these balance sheets, combined with potential interest rate hikes, is likely to be a challenge in terms of the stability of the financial markets.

«Healthy» interest rate hikes do not usually hurt

In conclusion, interest rate hikes are not necessarily bad for equities. If interest rates rise in times of intact economic growth, this can be considered a «healthy» rise. The economy and equity markets can cope with this without suffering damage. In this case, an interest rate hike can even be interpreted as a sign of strength.

Due to the «backlog» in monetary policy, the central banks do well to gain breathing room with healthy interest rate hikes and thus reduce the probability of one day standing with their backs against the wall. If this is successful, equities (and other risky assets) are a good investment, even in phases of interest rate hikes.

1 It concerns the return before inflation. Since interest rate hikes usually occur in periods of increased inflation, a loss of purchasing power may result in spite of positive returns. On average, inflation was 5.8% (YoY) in the period under review during interest rate hikes.